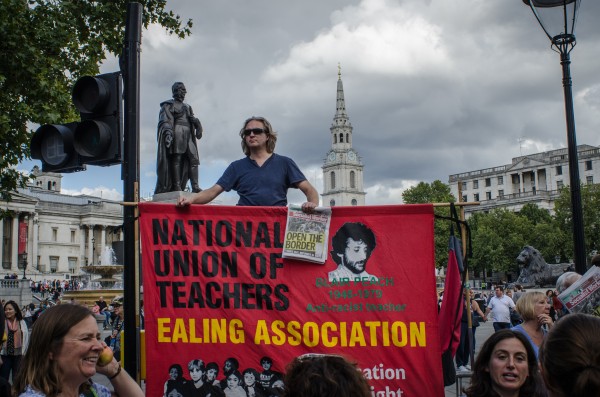

I went to the Refugee protest in London today. I got the train down from Birmingham in the morning. The train ticket alone cost more than the amount of money that asylum seekers in the UK get each week to live on (£36.95 per week). The protest was organised on Facebook. It started on Park Lane and then we walked to Parliament Square where newly elected Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn made a speech – his first political statement since winning Labour leadership three hours earlier. I don’t know how many thousands of people were there. I would guess around 50,000 at least.

This is 30,000 more people than Cameron has agreed to accept from the growing global refugee population. He announced last week that Britain would only accept 20,000 refugees over the next five years – and these would only be from Syria – which ignores the thousands of Afghans, Eritreans, Sudanese, and many other nationalities who are fleeing war, famine and conflict. Compared to the likes of Germany who have agreed to accept up to 800,000, this tiny number of refugees is laughable. Britain is punching well below its weight.

Walking along with the crowd of protesters, holding banners and shouting ‘Say it loud, say it clear, Refugees are welcome here‘, I must admit I found it quite emotional at times. In a good way. The joy on people’s faces. The possibility. The (naive?) thought that collective action might lead to change. Who am I kidding, I know that protests don’t work. Attending the 2003 anti-Iraq-war protest along with one Million other hopeful citizens taught me that.

I don’t know whether its the culmination of having seen the situation in Calais first hand recently, or just the scale of this emergency, but the affectual and emotive side of things came to a fore. Either way, it was wonderful to be among people who were singing from the same hymn sheet.

A Jeremy Corbyn supported holds pro-Corbyn leaflets, who was elected leader of the Labour Party this just hours earlier.

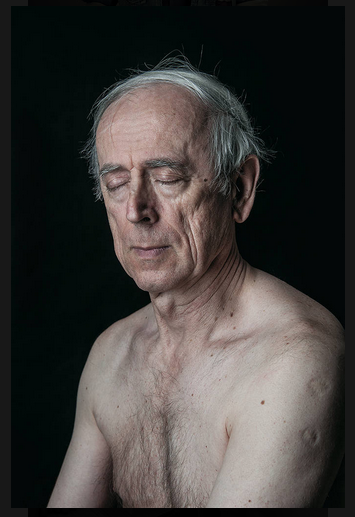

I was thrilled to be invited to showcase my portrait of a boy swimming in a river near Chernobyl, Ukraine, at this year’s Portrait Salon galler(ies). The Portrait Salon exhibition toured the UK throughout 2014 and 2015 and my portrait was exhibited in London, Edinburgh, Bradford, North Wales and Birmingham.

My photo was in great company and it was wonderful to see such an array of beautiful and thought provoking portraits in one place. The exhibition in Birmingham was at the Parkside Gallery at Birmingham City University.

The portrait shows a boy jumping out of a river that runs through the contaminated Chernobyl Nuclear Exclusion Zone in Ukraine.

Chernobyl Swimmer – exhibited in Portrait Salon Exhibition, part of my ‘Chernobyl: War without War’ series.

(You can see the whole ‘War without War’ Chernobyl series here)

Coincidentally, among the many striking photographs exhibited at Portrait Salon, was an image by Phil Le Gal. I had to good fortune to meet Phil in the Calais refugee camp recently as he worked on his ongoing project ‘The New Continent‘ (which is well worth following).

Phil Le Gal seen through his Medium Format camera, which I failed to focus properly! We met in the ‘New Jungle’ refugee camp in Calais.

Here is Phil’s excellent portrait that was also in the Portrait Salon Exhibition. The image is part of his series ‘Days of Mercy‘ which “attempts to decode the practice of ancient religious rituals deeply buried in the heart of Brittany“. Wonderful stuff.

I have been to many exhibitions before, but it was really exciting to see my own image among such a wonderful group of photographs!

Myself and colleagues at the University of Birmingham Dr Surindar Dhesi and Dr Arshad Isakjee, have conducted the first academic study of the ‘New Jungle’ refugee camp in Calais.This research has been funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC).

Our research intersects the fields of Public Health and Human Geography, and is revealing situation in Calais as a humanitarian crisis.

Read the text of our Conversation piece here:

***

As the sun sets on Calais, a new barbed wire fence glints in the evening light, casting a shadow over the growing migrant camp known as the “New Jungle”.

Through the thick undergrowth of what was once an industrial dumping ground, tents and tarpaulin structures stretch into the distance. These are the makeshift homes currently providing insufficient shelter from the elements for more than 3,000 refugees. On the other side of the fence, cars and lorries trundle towards the port of Calais – and the northern edge of the Schengen Area, where people can move freely across much of Europe.

With Operation Stack in full force, and the British prime minister, David Cameron, expressing “every sympathy with holidaymakers”, the body count at Calais quietly continues to rise. A migrant died on July 28 as he tried to reach the UK. He was the ninth person to lose his life to the Calais-Dover gauntlet between June and July.

Cameron has pledged that the UK government will do everything it can to deal with this situation, but sitting in the detritus of the Calais camp, it is clear that the real crisis is humanitarian and is being fatally overlooked.

We have made two visits to Calais, spending several days at a time interviewing the camp’s residents. Our research is revealing the desperate conditions in which they are living. It is time the UK and French governments took responsibility for a shared issue. So far, all migrants are being given is more barbed wire.

Life in Calais

“When I first got to the Jungle, I thought to myself: ‘is this really Europe?’” said Ilyas, a Sudanese migrant whose family were murdered byJanjaweed militia.

He showed us the rudimentary “kitchen” he uses to cook – a dusty tent propped up with branches, with no place to safely store food. Like many, he had taken the hard route to Europe, through the Sahara desert – where three of his fellow passengers perished – and then the equally deadly boat journey across the Mediterranean.

Ilyas’s friend showed us a shaky video he made on his phone of his eight-day sea crossing, this time from Egypt: “We did not have any water for three days,” he explained, flicking through his phone to show happier images of friends and family in the country he was forced to leave.

Their troubles did not end when they reached European soil. Migrants we met in Calais who landed on Italian shores report being abandoned by authorities. Young and able men, in particular, are kept in camps for no longer than a few days; many end up homeless and hungry on the streets of Italy. As Italian agencies struggle to cope with the record numbers of migrants crossing the Mediterranean, some report being explicitly told to travel to northern European countries such as France, Germany and the UK. Others say they have even been shown a map.

So a small minority of the 137,000 migrants who have arrived in Europe so far this year have ended up in Calais. The New Jungle – less than one square kilometre in area – is where thousands of migrants live in appalling conditions that would not meet any humanitarian standards.

Toilet facilities are limited. There are two dozen portaloos and a few wooden toilet blocks with no handwashing facilities. Piles of rubbish attract rats and other pests. There is only access to cold water, often at some distance from the ad hoc living spaces. It is unsurprising then that many residents told us they are suffering from fevers, stomach pains and diarrhoea.

Some residents of the camp use chemical containers to transport water to their tents – and every morning, men, women and children as young as ten can be seen queuing for hours for a rare opportunity to gain access to a shower. At every turn, migrants can be seen limping and bedraggled, visibly injured by the increasing risks they are taking to enter the UK. Others say they are victims of police brutality and local thugs. Médecins du Monde is doing excellent work in the camp, but the scale of injury and illness is increasing.

A global crisis

Calais is undoubtedly a humanitarian and public health crisis. Yet it is only a microcosm of the migration crisis as a whole. In the world today, a population the size of Italy has been forced from their homes, putting global numbers of refugees at a level not seen since the end of World War II.

Developing countries – not European nations – host most of them. Turkey alone gives refuge to 1.7m refugees from Syria. The next five countries hosting the largest numbers of refugees are Pakistan, Lebanon, Iran, Ethiopia and Jordan.

On the northern edge of the New Jungle, a huge bunker looms over the people queuing for a shower. Built during World War II to protect Hitler from invasion, it reminds us that this is not the first time Calais has been on the frontline of efforts to keep out perceived existential threats.

Britain’s home secretary, Theresa May, has pledged to spend another £7m to reinforce Fortress Calais with more barbed wire – and an archipelago of migrant camps is spreading across the continent. For her, and for the British government, this is a security threat. Spending time with the residents of the Calais camp however, things look starkly different. It’s time to wake up to the humanitarian crisis unfolding in the heart of Europe.

Authors: Dr Thom Davies, Dr Surindar Dhesi, Dr Arshad Isakjee

I was invited to present my PhD research about Chernobyl at UCL last June with Platform Ukraine, a multidisciplinary network set up in response to the recent tumultuous events in Ukraine and Eastern Europe. Platform Ukraine is based at the School of Slavonic and Eastern European Studies (SSEES).

The conference shone a timely light on many aspects of the post-Euromaidan situation in Ukraine, as well as providing an opportunity to exchange ideas on boarder issues and challenges in Post-Socialist space.

I was on a panel focusing on Chernobyl and was talking alongside Dr Paul Dorfman from UCL and Professor Jim Smith from the University of Portsmouth. Chaired by Mateusz Zatonski from London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the session lead to an interesting discussion about the role of nuclear power in contemporary society. Paul and Jim both gave excellent talks from a more scientific (with a capital ‘S’) perspective than my own ethnographic insights, which made for an interesting confluence of ideas.

My presentation was titled ‘Living with Nuclear disaster: Informal Understandings of Chernobyl‘.

Abstract:

"Drawing upon extensive qualitative research and visual methods with communities who live around the Exclusion Zone in Ukraine, this paper will discuss the ‘lived experience’ of nuclear disaster (de Certeau 1984). It will reveal the coping tactics and informal understandings of post-atomic space that allow marginalised groups to inhabit and renegotiate this stigmatised landscape. The paper argues that alongside the half-lives, Exclusion Zones and official measurements of nuclear risk, exists an informal geography of Chernobyl. Local alternative understandings of Chernobyl, which are often at odds with the formalised spatialisations of the Zone, allow people to negotiate the twin ‘exposures’ of nuclear radiation and de facto state abandonment. Informal economic activities such as border crossing, mushroom picking, and scrap metal collection blur the boundaries of the Zone and contest the official governance of Chernobyl (Davies & Polese 2015). This long-term research has involved participant observation, participatory visual methods, and semi-structured interviews with evacuees, liquidators, border guards, ‘Chernobyl widows’, farmers and returnees who inhabit and contest the nuclear borders of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone."

Being part of Platform Ukraine was a excellent experience and I look forward to more involvement in the future.

You can check out their blog and follow Platform Ukraine on twitter here.

I use photography as part of my research practice, both to gain access to hidden spaces and communities, and to illustrate and communicate my ethnographic data once no longer in ‘the field’.

One of my photographs from my Chernobyl research was selected for the Images of Research exhibition at the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. It shows one of the informal activities I witnessed and researched near the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone in Ukraine.

A woman crosses the barbed wire fence into the contaminated nuclear Zone. Beyond her a track used by border guards to monitor and prevent trespassers runs parallel to the fence, and beyond that the contaminated forest of the Zone:

Many people informally enter the Exclusion Zone to collect scrap metal to sell on the black market, or to gather wild foods such as berries, mushrooms, and wild game to eat and sell. I spent long time learning from people who contest the official borders of the Zone, using a research method known as participant observation. Through participatory visual methods (which you can read about here) and many interviews with people who live near Chernobyl, I learnt about their alternative understandings of radiation risk and their complex relationship with place. You can read more about my academic research into the human geography of Chernobyl in these two papers:

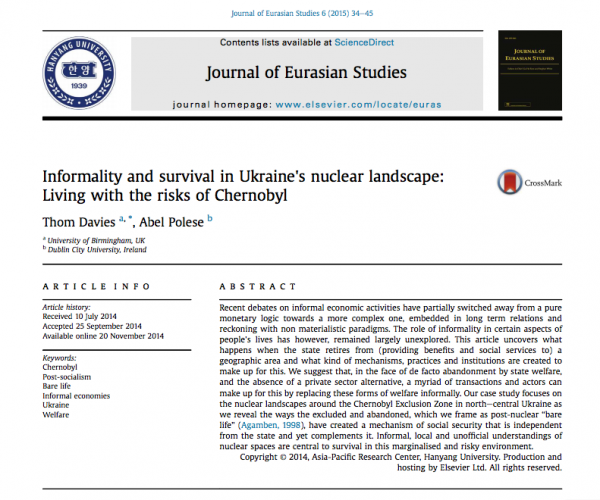

Informality and Survival in Ukraine’s Nuclear Landscape: Living with the Risks of Chernobyl by Davies & Polese (2015)

A Visual Geography of Chernobyl: Double Exposure by Davies (2013)

Here is a quote from my research that relates to the image above:

"We know there is radiation there, and police say 'Don't go there, there is radiation'. On the fence there is a sign that says there is radiation: 'Don't go in, there is radiation'. But we go...Blueberries, blackberries..."* * *

The Images of Research exhibition is free to view at the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery from 16th-22nd March 2015.

# Chernobyl, exhibition, gallery, Images of research, participant observation, photography, visual methods

0 0

Midway through February I had my first taste of normality since last year: a day off! Feels amazing. The final death throes of thesis writing have been incredibly focused and stressful, so it was really wonderful to not be staring at a computer screen writing about Chernobyl. I’m fascinated by the nuclear disaster, but its good to come up for air.

Writing about Ukraine while in the UK, along with seeing the conveyor belt of media coverage that Ukraine has experienced, has made me feel nostalgic for Eastern Europe. The geographer Cindi Katz reminds us that there’s little distinction between the place of ‘fieldwork’ (for me, Ukraine) and the geographically separate yet emotionally connected spaces of writing. In the age of social media especially, the borders between ‘the field’ and home have become comprehensively blurred.

Since I left Ukraine in late 2013 – days before the Euromaidan revolution – the borders of Ukraine have been permanently changed, and I have been constantly reminded of the place I grew to know. Ukraine ‘experts’ have crawled out of the woodwork, and many photographers have cast their lens on a country that for so long was overshadowed by its larger neighbor to the East. This visual narrative of post-revolution Ukraine has remained unsurpassed, in my opinion, by Anastasia Taylor-Lind’s fantastic project ‘Portraits from the Black Square’ (made with assistance from Emine Ziyatdinova), but times have moved on, and homegrown photographers especially are making incredible images that cast our imaginations towards a once sidelined country. For example my friend Anastasia Vlasova’s striking portrait from earlier this month of the evacuation of the encircled town of Debaltseve.

I will write a more substantive blog post after I submit my thesis on the contemporary visual landscape of Ukraine. Its worth viewing Chris Nunn’s work for example, which has been a pleasure to see evolve.

For the last year I’ve been exposed to the everyday reality of thesis writing (not fun), where thinking about Ukraine has in some senses been a job. Doing this against a backdrop of the visual barrage of Ukraine-focused coverage has brought its own challenges.

Today I saw Oksana Yushko’s thought provoking project about love between Ukrianian and Russian couples, featured in the New York Times. The way it addresses the current conflict in Ukraine, avoiding the tired clichés of camouflage clad soldiers and frontline bravado was a breath of fresh air. It reminded me that not only photographers but also academics need to rise to the challenge of articulating Ukraine differently. It reminded me also that now, more than ever on this first ‘day off’, I feel a longing to reconnect with my own experiences in Ukraine. My experiences, which spread over several years, were characterized just as must by the mundanity of everyday life, as by the adventures and scrapes I had while in Chernobyl. Oksana (with assistance from husband Arthur Bondar) captures something of this prosaic normalcy that characterizes most of life in Ukraine (as elsewhere), and is perhaps understandably missing from Ukraine’s post-revolution visual narrative; Alla and Sergey’s family relaxing in their lounge; Tatiyana and Sergei hanging washing on the line; Dima and Vlada sitting by the stove in their kitchen:

Photograph by Oksana Yushko © from her ongoing project ‘Familia‘

Making Borscht

My time in Ukraine was often centred around people, connections, laughter, and food. On my day off I wanted to make something that would remind me of Ukraine. And like Oksana Yushko’s project that photographs couples from both sides of the Ukraine-Russia border, I went for a dish that is synonymous with both these Slavic countries: Borscht.

Having been served this delicious soup countless times in Ukraine yet paid shamefully little attention to how it is actually made, I looked to this Guardian article for a recipe, and was really pleased with the results (I doubled the below ingredients to serve eight people). Its also a red soup, so its an ideal dish (very tenuously!) for Valentine’s day…

Given the cultural importance of this dish in Ukraine (and Russia), I wouldn’t be surprised if it has inspired academic attention from anthropologists and the like, much like Nancy Ries focusses on the potato to talk about post-Soviet survival in Russia. But I digress.

Ingredients:

-

300g beetroot, peeled

50g butter

1 small onion, 1 small carrot, 1 stick of celery, 1 small leek, all peeled where necessary and cut into small dice or rings

2 grains allspice

½ bay leaf

1.5l gelatinous beef stock

2 medium floury potatoes, eg Maris Piper, peeled and cut into small dice

½ small cabbage, shredded

4 cloves garlic, peeled and crushed

2 tbsp cider vinegar

1 tsp sugar

½ tsp ground black pepper

Sour cream and fresh dill, to serve

Full the full ‘imagined geography’ experience, why not one or two glasses of Ukrainian vodka?

The borscht tasted delicious and reminded me of Ukraine, which I guess was the whole point. When I finish the PhD and start writing papers about my Fukushima research I think I will have to learn how to cook Ramen. But until then, I’m going to eat another bowl of borscht – its back to the thesis tomorrow.

I have just published an academic article about Chernobyl in the Journal of Eurasian Studies. You can view the paper here.

I have been working on the ideas in this paper for some years, first sketching some initial thoughts while sitting in a flat in north Kyiv, Ukraine. The view from the balcony of that apartment can be seen in a ‘lomo’ panorama photograph below. It’s nice to see these ideas put through the academic grinding mill of peer review and finally end up in a paper.

Being new to academia I am still amazed how it takes so long to publish an academic article. And I don’t just mean the final stages of publication like dealing with the editor’s final comments, reformatting citation bibliographies and re-checking ‘uncorrected proofs’. I mean the whole thing: collecting the data; making sense of it; sketching out ideas; drafting; re-drafting and writing the damn thing; sending it off for peer review; and then the long months of waiting before the inevitable and sometimes frustrating reviewers’ comments.

I’m sure the whole process gets quicker with experience, but nevertheless, when I think back to the first drafts of my academic outputs it seems an age ago.

Academic Capital?

Academics don’t get paid to publish, in a direct way at least. That kind of encouragement would be superfluous. They’re like amateur photographers or part time models: promised ‘exposure’ in exchange for free work. Instead their publications become notches on their academic bedposts, to be spun out on loquacious CVs and dropped into departmental conversation. Perhaps these notches will be read by other academics, and cited in their publications. The more citations the better! And perhaps they could use these highly cited papers to get a promotion, secure research funding, or move to a more prestigious department.

Like any business, academia is an incredibly competitive industry. This explains why publishers don’t need to pay academics to write articles, even ones that take years to create. Academics are chomping at the bit – they need to publish, they have to: ‘Publish or perish‘ goes the saying, and its true. Papers are academic capital.

And so, in a tentative step towards joining in, I’ve published another article.

Thom was paid in no way for publishing this blog post.

(You can view my very modest academic contributions here.)

I’m really thrilled to have one of photographs from my Chernobyl research featured in this years’ Portrait Salon exhibition – a real honour to have my photo in the company of such a talented group of photographers.

Its a great feeling that an image I made while standing waste deep in a river in the nuclear landscape of Chernobyl in Ukraine will be seen by people in galleries in the UK. Photography and PhD research are both quite isolating adventures at times, so its nice to have the opportunity to shed light on a small aspect of my research. I am looking forward to seeing the show myself when it comes to Birmingham next July.

The annual Portrait Salon exhibition was created in 2011 by Carole Evans and James O Jenkins and is a response to the Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize. It showcases photographs rejected from this prestigious competition. (Read a review of this year’s Taylor Wessing Prize by Lewis Bush on the Disphotic blog here.)

As described in an article on the British Journal of Photography:

‘The idea [for Portrait Salon] is based on the first Salon des Refusés that was staged by artists who were rejected from the 1863 Paris Salon. However, as Evans and O Jenkins point out, many rejected works went on to gain significant notoriety, a prime example being Édouard Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe. “This goes to show that juried art shows don’t necessarily reflect the views of the public or predict what will become memorable”, the founders comment.’

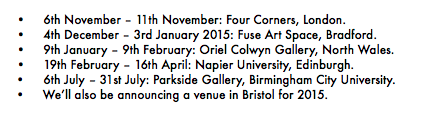

The Portrait Salon exhibition will run through 2014 – 2015 and will tour gallery spaces in London, Brighton, Bradford, North Wales, Edinburgh, Birmingham and Bristol.

Below are some other photographs from the group exhibition that caught my eye. Check out all the images here.

Photograph of Ian McKellen by Rory Lewis rorylewis.co.uk

I like how this photograph captures that awkward liminality of being a teenager. The look the kid with the red hoodie is giving Sophie is great. By Sophie Gerrard sophiegerrard.com

A striking portrait by Ania Mroczkowska aniamphotography.com

A school boy in a chip shop photographed by Sophie Green. Her other project called ‘I am Sophie Green’ where she photographs other people called ‘Sophie Green’ is worth viewing too. By Sophie Green sophiegreenphotography.com

One of the two portraits that Jack Davidson has in this year’s Portrait Salon exhibition. It reminds me of Spencer Murphy’s photograph that won the Taylor Wessing prize in 2013. By Jack Davidson jackdavison.co.uk

This photo of a breast feeding mother at a bus stop reminded me of renaissance paintings of Modonna and child. By Valentina Schivardi valentinaschivardi.com

I don’t know where this photograph was taken but the wallpaper in the background reminded me of homes in Ukraine. By Jill Wooster jillwooster.com

A portrait of Charlotte Church by Clare Hewitt clarehewitt.co.uk

These are the dates and location of the exhibition:

‘Amateur Photography as an Aid in Teaching Geography’

“Nowadays the camera and the bicycle go everywhere hand in hand. The cyclist has splendid opportunities for photography, and photography is a pleasant addition to the cyclist’s enjoyment. With these two machines the teacher of Geography can do some good solid work. In the camera particularly [s]he will find a valuable friend and helper. Although many teachers still delight in the long lists of old-fashioned text-books, yet many are trying to vivify their work instead of presenting a mass of dry bones. They know that there is no subject on which boys [sic] can be keener, and they will find the camera a great aid in their present uphill task of teaching a subject which rarely receives the recognition it deserves”

C. Carter (1901) The Geographical Teacher Vol. 1. No. 1 pp. 27

To read this charmingly antique yet prescient article click here.

The journal The Geographical Teacher ran from 1901 – 1926. This first article shows the central importance of the visual image, and especially the photograph, in the academic study of geography; a discipline which to this day “rarely receives the recognition it deserves”. It is interesting that Carter here links the emerging middle-class pursuit of photography with another bourgeois device of mobility – the bicycle. The camera and the bicycle would go on to have profound and far reaching impacts on the century that The Geographical Teacher had just begun to publish in.

The camera is a geography machine.

Research diary outtake:

Hazmat suits and dosimeters, masks and rubber gloves we walked. Through the woodland near their house, abandoned but not forgotten in the Exclusion Zone. I am shown where they used to live, before everything changed.

I am walking with a husband and wife who were forced to leave their home after the nuclear disaster. Like tens of thousands of other evacuees, their lives have been utterly disrupted by what happened at the local atomic power station.

Now uncertainty has become the new normal; of not knowing when or if they may ever return. Uprooted and downsized they now live several hours away, their children forbidden from making this post-atomic journey back to their abandoned home, which they check upon from time to time.

“Wild boar smashed through this window” I am told, and I’m shown the shattered glass inside their house where pigs have run amok. I had seen one earlier as we were driving down an unkempt street near Namie town, before it darted into the bushes.

Along a road left overgrown with years of moss and fallen trees, we climb like spacemen up through the forest: across a river, under a branch, down-wind of the nuclear plant. Our sartorial façades of disposable white clothing turn us into nuclear symbols, alien life in this beautiful wasteland. The only visibly ‘nuclear’ thing out here is us.

I am shown a plant and its unripened berries, held in a latex glove; I make a photograph, transfixed by this strange vista.

The sound of the waterfall and the wind-blown leaves fail to conceal the threat of radiation. The nagging ‘click’ of the Geiger counters make sure of that. We hold onto our dosimeters like handrails in the dark, as they guide us arrogantly across this nuclear landscape. Along with our protective clothing, these devices were lent to us by the sad-faced employees of ‘Tokyo Electric Power Company’ when we entered the Zone.

That evening as we leave the Zone and our bodies are scanned for radiation, the same nuclear workers will bend double, bowing deep apologetic bows – the likes of which I have not yet seen in Japan.

hazmat

ˈhazmat/

noun

-

dangerous substances; hazardous material.

-

A hazmat suit (hazardous materials suit) is a piece of personal protective equipment that consists of an impermeable whole-body garment worn as protection against hazardous materials. Such suitsare often combined with self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) to ensure a supply of breathable air.

# dosimeter, Exclusion Zone, Fukushima, Geiger, Hazmat, human geography, Nuclear, radiation, TEPCO

1 1