I use photography as part of my research practice, both to gain access to hidden spaces and communities, and to illustrate and communicate my ethnographic data once no longer in ‘the field’.

One of my photographs from my Chernobyl research was selected for the Images of Research exhibition at the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. It shows one of the informal activities I witnessed and researched near the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone in Ukraine.

A woman crosses the barbed wire fence into the contaminated nuclear Zone. Beyond her a track used by border guards to monitor and prevent trespassers runs parallel to the fence, and beyond that the contaminated forest of the Zone:

Many people informally enter the Exclusion Zone to collect scrap metal to sell on the black market, or to gather wild foods such as berries, mushrooms, and wild game to eat and sell. I spent long time learning from people who contest the official borders of the Zone, using a research method known as participant observation. Through participatory visual methods (which you can read about here) and many interviews with people who live near Chernobyl, I learnt about their alternative understandings of radiation risk and their complex relationship with place. You can read more about my academic research into the human geography of Chernobyl in these two papers:

Informality and Survival in Ukraine’s Nuclear Landscape: Living with the Risks of Chernobyl by Davies & Polese (2015)

A Visual Geography of Chernobyl: Double Exposure by Davies (2013)

Here is a quote from my research that relates to the image above:

"We know there is radiation there, and police say 'Don't go there, there is radiation'. On the fence there is a sign that says there is radiation: 'Don't go in, there is radiation'. But we go...Blueberries, blackberries..."* * *

The Images of Research exhibition is free to view at the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery from 16th-22nd March 2015.

# Chernobyl, exhibition, gallery, Images of research, participant observation, photography, visual methods

0 0

Midway through February I had my first taste of normality since last year: a day off! Feels amazing. The final death throes of thesis writing have been incredibly focused and stressful, so it was really wonderful to not be staring at a computer screen writing about Chernobyl. I’m fascinated by the nuclear disaster, but its good to come up for air.

Writing about Ukraine while in the UK, along with seeing the conveyor belt of media coverage that Ukraine has experienced, has made me feel nostalgic for Eastern Europe. The geographer Cindi Katz reminds us that there’s little distinction between the place of ‘fieldwork’ (for me, Ukraine) and the geographically separate yet emotionally connected spaces of writing. In the age of social media especially, the borders between ‘the field’ and home have become comprehensively blurred.

Since I left Ukraine in late 2013 – days before the Euromaidan revolution – the borders of Ukraine have been permanently changed, and I have been constantly reminded of the place I grew to know. Ukraine ‘experts’ have crawled out of the woodwork, and many photographers have cast their lens on a country that for so long was overshadowed by its larger neighbor to the East. This visual narrative of post-revolution Ukraine has remained unsurpassed, in my opinion, by Anastasia Taylor-Lind’s fantastic project ‘Portraits from the Black Square’ (made with assistance from Emine Ziyatdinova), but times have moved on, and homegrown photographers especially are making incredible images that cast our imaginations towards a once sidelined country. For example my friend Anastasia Vlasova’s striking portrait from earlier this month of the evacuation of the encircled town of Debaltseve.

I will write a more substantive blog post after I submit my thesis on the contemporary visual landscape of Ukraine. Its worth viewing Chris Nunn’s work for example, which has been a pleasure to see evolve.

For the last year I’ve been exposed to the everyday reality of thesis writing (not fun), where thinking about Ukraine has in some senses been a job. Doing this against a backdrop of the visual barrage of Ukraine-focused coverage has brought its own challenges.

Today I saw Oksana Yushko’s thought provoking project about love between Ukrianian and Russian couples, featured in the New York Times. The way it addresses the current conflict in Ukraine, avoiding the tired clichés of camouflage clad soldiers and frontline bravado was a breath of fresh air. It reminded me that not only photographers but also academics need to rise to the challenge of articulating Ukraine differently. It reminded me also that now, more than ever on this first ‘day off’, I feel a longing to reconnect with my own experiences in Ukraine. My experiences, which spread over several years, were characterized just as must by the mundanity of everyday life, as by the adventures and scrapes I had while in Chernobyl. Oksana (with assistance from husband Arthur Bondar) captures something of this prosaic normalcy that characterizes most of life in Ukraine (as elsewhere), and is perhaps understandably missing from Ukraine’s post-revolution visual narrative; Alla and Sergey’s family relaxing in their lounge; Tatiyana and Sergei hanging washing on the line; Dima and Vlada sitting by the stove in their kitchen:

Photograph by Oksana Yushko © from her ongoing project ‘Familia‘

Making Borscht

My time in Ukraine was often centred around people, connections, laughter, and food. On my day off I wanted to make something that would remind me of Ukraine. And like Oksana Yushko’s project that photographs couples from both sides of the Ukraine-Russia border, I went for a dish that is synonymous with both these Slavic countries: Borscht.

Having been served this delicious soup countless times in Ukraine yet paid shamefully little attention to how it is actually made, I looked to this Guardian article for a recipe, and was really pleased with the results (I doubled the below ingredients to serve eight people). Its also a red soup, so its an ideal dish (very tenuously!) for Valentine’s day…

Given the cultural importance of this dish in Ukraine (and Russia), I wouldn’t be surprised if it has inspired academic attention from anthropologists and the like, much like Nancy Ries focusses on the potato to talk about post-Soviet survival in Russia. But I digress.

Ingredients:

-

300g beetroot, peeled

50g butter

1 small onion, 1 small carrot, 1 stick of celery, 1 small leek, all peeled where necessary and cut into small dice or rings

2 grains allspice

½ bay leaf

1.5l gelatinous beef stock

2 medium floury potatoes, eg Maris Piper, peeled and cut into small dice

½ small cabbage, shredded

4 cloves garlic, peeled and crushed

2 tbsp cider vinegar

1 tsp sugar

½ tsp ground black pepper

Sour cream and fresh dill, to serve

Full the full ‘imagined geography’ experience, why not one or two glasses of Ukrainian vodka?

The borscht tasted delicious and reminded me of Ukraine, which I guess was the whole point. When I finish the PhD and start writing papers about my Fukushima research I think I will have to learn how to cook Ramen. But until then, I’m going to eat another bowl of borscht – its back to the thesis tomorrow.

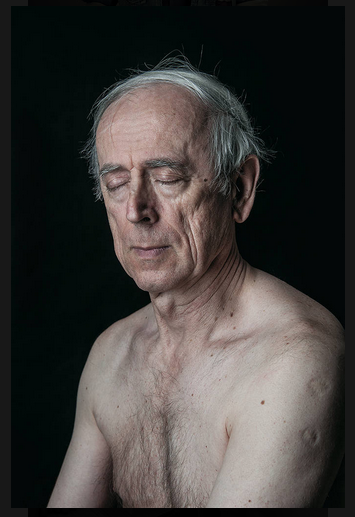

I’m really thrilled to have one of photographs from my Chernobyl research featured in this years’ Portrait Salon exhibition – a real honour to have my photo in the company of such a talented group of photographers.

Its a great feeling that an image I made while standing waste deep in a river in the nuclear landscape of Chernobyl in Ukraine will be seen by people in galleries in the UK. Photography and PhD research are both quite isolating adventures at times, so its nice to have the opportunity to shed light on a small aspect of my research. I am looking forward to seeing the show myself when it comes to Birmingham next July.

The annual Portrait Salon exhibition was created in 2011 by Carole Evans and James O Jenkins and is a response to the Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize. It showcases photographs rejected from this prestigious competition. (Read a review of this year’s Taylor Wessing Prize by Lewis Bush on the Disphotic blog here.)

As described in an article on the British Journal of Photography:

‘The idea [for Portrait Salon] is based on the first Salon des Refusés that was staged by artists who were rejected from the 1863 Paris Salon. However, as Evans and O Jenkins point out, many rejected works went on to gain significant notoriety, a prime example being Édouard Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe. “This goes to show that juried art shows don’t necessarily reflect the views of the public or predict what will become memorable”, the founders comment.’

The Portrait Salon exhibition will run through 2014 – 2015 and will tour gallery spaces in London, Brighton, Bradford, North Wales, Edinburgh, Birmingham and Bristol.

Below are some other photographs from the group exhibition that caught my eye. Check out all the images here.

Photograph of Ian McKellen by Rory Lewis rorylewis.co.uk

I like how this photograph captures that awkward liminality of being a teenager. The look the kid with the red hoodie is giving Sophie is great. By Sophie Gerrard sophiegerrard.com

A striking portrait by Ania Mroczkowska aniamphotography.com

A school boy in a chip shop photographed by Sophie Green. Her other project called ‘I am Sophie Green’ where she photographs other people called ‘Sophie Green’ is worth viewing too. By Sophie Green sophiegreenphotography.com

One of the two portraits that Jack Davidson has in this year’s Portrait Salon exhibition. It reminds me of Spencer Murphy’s photograph that won the Taylor Wessing prize in 2013. By Jack Davidson jackdavison.co.uk

This photo of a breast feeding mother at a bus stop reminded me of renaissance paintings of Modonna and child. By Valentina Schivardi valentinaschivardi.com

I don’t know where this photograph was taken but the wallpaper in the background reminded me of homes in Ukraine. By Jill Wooster jillwooster.com

A portrait of Charlotte Church by Clare Hewitt clarehewitt.co.uk

These are the dates and location of the exhibition:

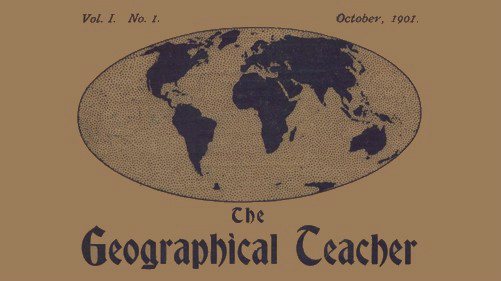

‘Amateur Photography as an Aid in Teaching Geography’

“Nowadays the camera and the bicycle go everywhere hand in hand. The cyclist has splendid opportunities for photography, and photography is a pleasant addition to the cyclist’s enjoyment. With these two machines the teacher of Geography can do some good solid work. In the camera particularly [s]he will find a valuable friend and helper. Although many teachers still delight in the long lists of old-fashioned text-books, yet many are trying to vivify their work instead of presenting a mass of dry bones. They know that there is no subject on which boys [sic] can be keener, and they will find the camera a great aid in their present uphill task of teaching a subject which rarely receives the recognition it deserves”

C. Carter (1901) The Geographical Teacher Vol. 1. No. 1 pp. 27

To read this charmingly antique yet prescient article click here.

The journal The Geographical Teacher ran from 1901 – 1926. This first article shows the central importance of the visual image, and especially the photograph, in the academic study of geography; a discipline which to this day “rarely receives the recognition it deserves”. It is interesting that Carter here links the emerging middle-class pursuit of photography with another bourgeois device of mobility – the bicycle. The camera and the bicycle would go on to have profound and far reaching impacts on the century that The Geographical Teacher had just begun to publish in.

The camera is a geography machine.

On words and photography:

Putting words with photographs, especially quotations from interviews, can often change the meaning of an image. I was reminded of this recently when I visited the Photographer’s Gallery in London to see an exhibition about early Russian colour photography (reviewed by Lewis Bush here). Not least due to my ignorance of Russian photographic history, it was not until I read the captions, titles and image-descriptions that the photographs made sense; words changed their meanings.

I have hundreds of hours of recorded interviews with people who live near Chernobyl in Ukraine. They sit transcribed on my laptop, slowly working their way into my PhD thesis. I have started working on a small project called Chernobyl Interiors that matches some of these quotations with photographs I made in the intimate spaces of the participants’ houses around the Exclusion Zone.

So often Chernobyl is portrayed photographically as an abandoned, ‘dead’ and decaying place, but it is a landscape that people live with. It is home to many people who dwell in the shadow of uncertainty and nuclear pollution, but also by people who laugh, cry, fall in love and live lives that we would all recognise.

The photographs, like the one above are nothing special; they are rather banal interior shots of the homes I was invited into. But put next to quotations from people who live in these houses and they are transformed – perhaps even seen differently:

“My son was 23 and the other was 24

when they died. It was radiation from

Chernobyl.

I used to sing and play the accordion in

the local house of culture, but now

that my children are dead I don’t sing

anymore”

I remember this interview very well, a sad story of suffering and loss that was far from unique in this nuclear landscape. Though the quotation above gives no more than a ‘snapshot’ into this mother’s wider story, it also gives the photograph a new significance, and perhaps provides a deeper way of narrating the ongoing story of Chernobyl.

Susan Sontag – one of the more prominent scholars of photography – said:

“Photographs – and quotations – seem, because they are taken to be pieces of reality, more authentic than extended literary narratives”

There is an advantage of only seeing (or reading) a snapshot of a complex story; it discards the clutter and complexities of everyday life, distilling and framing a message to the viewer in a particular way. But with this comes its own set of problems. Photographs hide as much than they reveal: at best – sanitizing reality – at worst – changing it.

Photography, perhaps more than any other medium of communication, lays bare what Feminist-theorist Donna Haraway calls our ‘positionality’: The idea that all knowledge – be it contained within a photograph or in academic discourse – is created by individuals who are ‘situated’ with their own subjective perspectives and embedded within power structures that influence the creation of that situated knowledge.

Moreover, photography contains a unique disconnect – that photographs can simultaneously be both ‘fact’ and ‘subjection’. There is an unresolved tension between photography’s use to document ‘data’ (crime scenes, mugshots, war photojournalism, ‘evidence’ etc.), and the highly positioned nature of each photograph being a personal and curated slice of reality: each time a photographer raises the camera to their face to frame a picture they make a subjective choice.

Street photographer Garry Winogrand once commented on photography that:

“putting four edges around a collection of information or facts transforms it”

Of course the same can be said about a quote from an interview. Instead of four edges we use quotation marks, composing the spoken word from a choice of baggier utterances, leaving unwanted information outside the verbal frame.

In Chernobyl Interiors I want to be reflexive about this process, as both the images and quotes have been framed by my situated self. This is in contrast to my other Chernobyl project Disposable Citizens, in which people were given disposable film cameras to document their own lives and give their own view of their world.

The title of the exhibition I visited on early Russian colour photography was ‘Primrose’. I did not understand the significance of this until I watched an interview with the curator Olga Sviblova. She explained that Primroses are often the first flowers to bloom in the thaw of Spring after the long snow-covered darkness of Russian winters. They bring colour into Russia’s monochrome landscape. “Its like the sun arriving from the earth” she said, and with those words, it made sense.

# Chernobyl, Chernobyl Interiors, Gary Winogrand, photography, positionality, Susan Sontag

0 0

Vodka reflections:

I’m editing photographs from my research trips to Chernobyl in Ukraine. Tomorrow will mark the 28th anniversary of the disaster. Going through the photographs and interviews from Ukraine is reminding me of some of the most incredible experiences of my life, and the kindest people I know.I’m working late tonight to meet deadlines, but at 1:23am I will raise a glass of Nemiroff vodka to all those who were (and continue to be) affected by the disaster. Especially those I had the pleasure of knowing – some of whom are no longer here.

The photograph on the laptop above is part of the War without War photography project. It shows a photograph of Sasha, a great man I had the pleasure of spending time with.